Mastoiditis

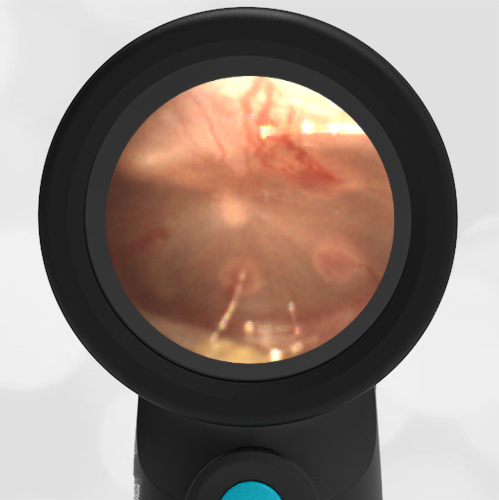

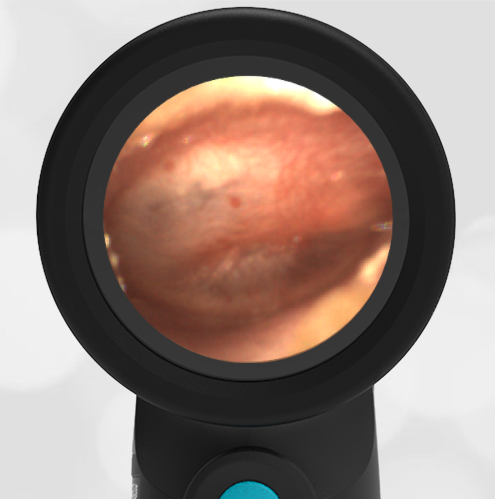

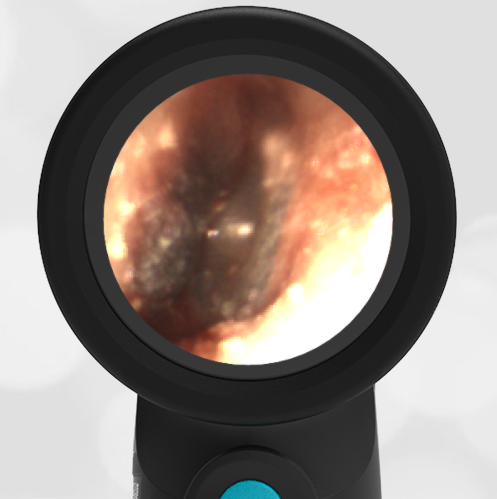

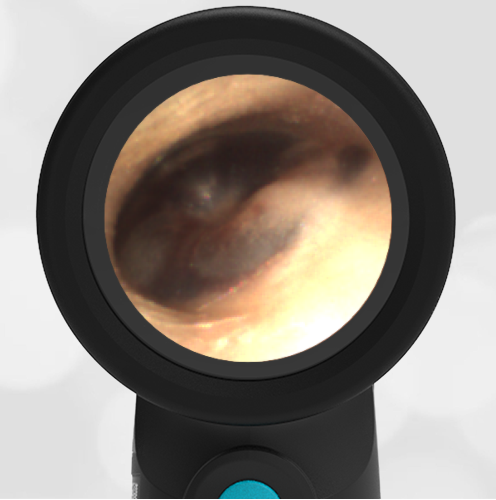

A 3-year-old male presents to the emergency department with ear pain. The parents report their son has had fever for “at least a week” with temperatures up to 104 F. He was seen in Urgent Care at the onset of his febrile illness where he was diagnosed with acute otitis media and started on an antibiotic. Upon physical exam the child has a temperature of 102.5 and mild nasal congestion without purulent drainage. He is very tender to palpation in the area posterior to his left ear where there is also distinct erythema and warmth of the skin. The external ear appears normal and his Wispr exam is below. The remainder of his exam is non-focal for a source of his fever.

Which of the following is true regarding the child’s condition?

- Continue the antibiotic prescribed by urgent care.

- It is the most common serious complication of acute otitis media (AOM).

- This condition is seen more frequently in adults than children.

- A CT scan is usually needed to guide treatment.

2. It is the most common serious complication of acute otitis media (AOM).

This child has acute otitis media (AOM) in his left ear and is presenting with signs and symptoms consistent with acute mastoiditis (AM), the most common complication of middle ear infections. While rare, affecting approximately 0.25% of AOM cases, the incidence of AM has increased over the past two decades likely attributable to increasing antibiotic resistance. The child’s continued AOM despite recent treatment with an appropriate course of antibiotics is suggestive of the presence of a resistant organism.

Young children, particularly less than 3 years of age, are more prone to developing AM due to immunologic, epidemiologic, and anatomic features unique to pediatrics. Anatomic factors including greater pneumatization of the mastoid bone as well as a smaller aditus ad antrum (the opening between the middle ear and the mastoid space) appear to play a central role. AOM leads to edema and debris blocking the aditus ad antrum, preventing the purulent drainage from exiting the mastoid air cells. If not treated properly this “otomastoiditis” may then progress to boney destruction and osteomyelitis formation as well as an array of other described complications including boney (subperiosteal abscess), vascular (internal jugular thrombosis), neurologic (facial nerve palsy), or intracranial (epidural abscess or sinus thrombosis) locations.

Younger age appears to be a risk factor for these complications and accentuates the importance of a thorough history and physical exam, even with the occasionally mundane complaint of “ear pain”. This is especially true since the signs and symptoms of uncomplicated AM generally do not differ from those of AOM. Suspicion is raised by persistent fever and more severe complaints or tenderness, erythema, and swelling in the poster auricular area—signs that may occur even in cases where there is still no complete erosion of the cortical bone or purulent collection. In more progressed cases, there may be anterior displacement of the auricle due to the evolving edema and associated cellulitis. Some experienced clinicians feel comfortable with diagnosing AM based on these physical findings, while many still rely on CT scans to evaluate for evidence of osteomyelitis or other any other complicating pathology noted above.

Management of AM includes initiation of IV antibiotics, typically a third-generation cephalosporin to extend coverage against resistant organisms. The placement of tympanostomy tubes may aid in resolution and allows culturing of middle ear fluid to guide further antibiotic therapy. Close monitoring in the hospital is required to assess the response to this therapy and anticipate additional surgical management for any indication of extension.

Here is the complete video exam:

Reference:

Pasquale Cassano, Giorgio Ciprandi, and Desiderio Passali. Acute mastoiditis in children. Acta Biomed, 2020; 91(Suppl 1): 54–59.